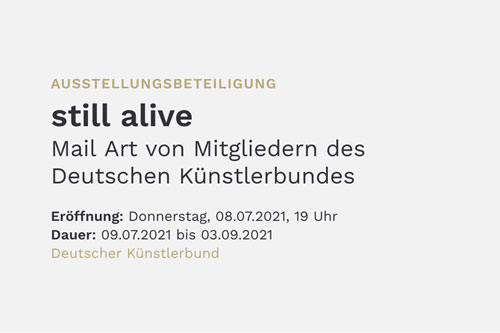

still alive

AUSSTELLUNGSBETEILIGUNG

still alive

Mail Art von Mitgliedern des Deutschen Künstlerbundes

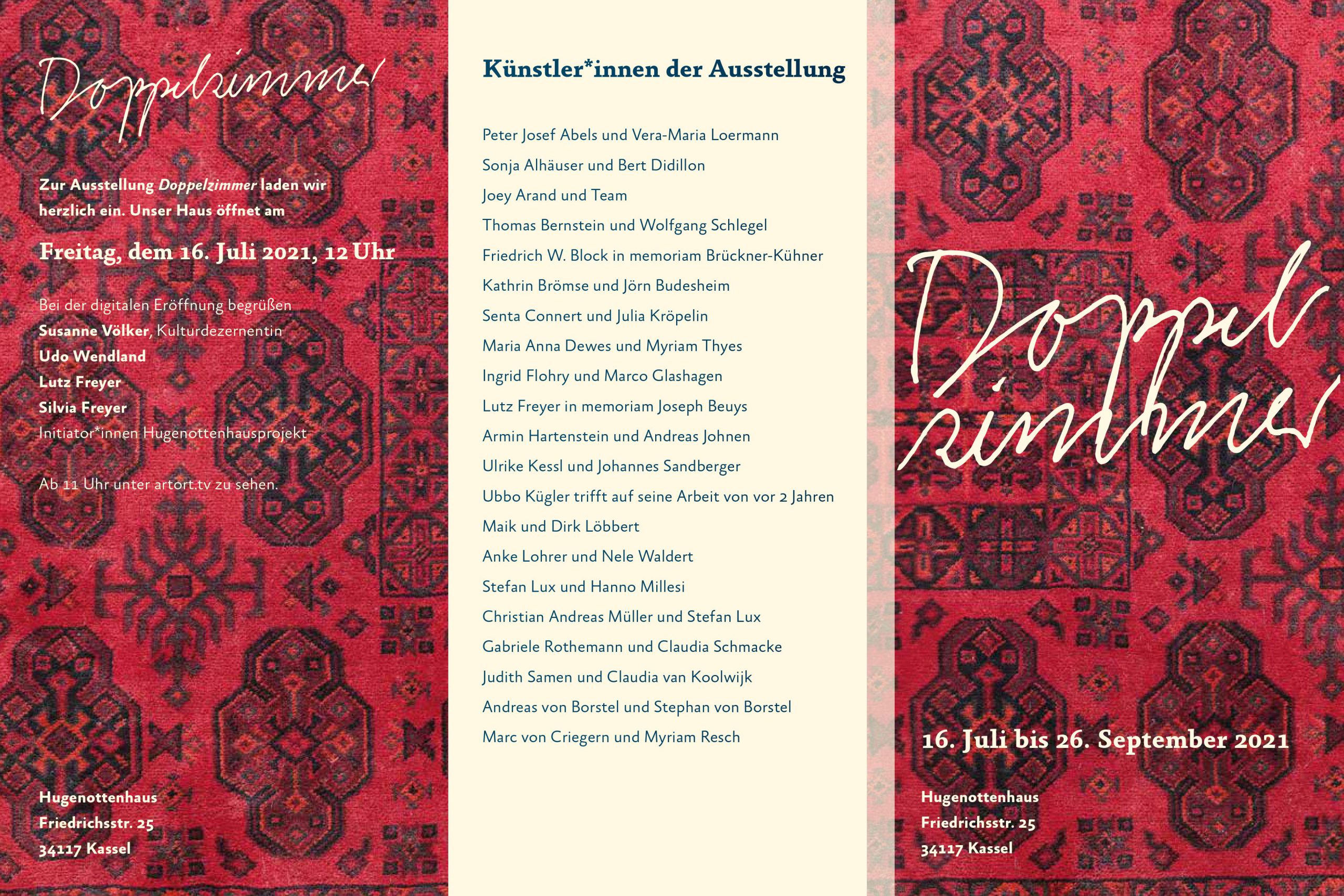

Doppelzimmer

AUSSTELLUNG

In Präsenz und Abwesenheit

„In Präsenz und Abwesenheit“ (Objekt, Zeichnung, Video, Sound) ist eine multimediale Installation, die zusammen mit Johannes Sandberger in der Ausstellung „Doppelzimmer“ zu sehen war. Die Objekte der beiden und sind nur im Video zu sehen, im Wechsel mit Kamerafahrten durch den Raum, einige wenige sind auch auf den Zeichnungen zu sehen. Der Sound ist von Johannes Sandberger, drei Loops unterschiedlicher Länge mischen sich immer wieder neu.

Hugenottenhaus

Friedrichsstrasse 25

34117 Kassel

16. Juli bis 26. September 2021

Die Künstlerliste und weitere Informationen unter:

hugenottenhaus.com

Fliegende Stühle

AUSSTELLUNG

Kunst-Radroute „FahrArt“

Fliegende Stühle, De Wittsee, Nettetal

Am Wittsee 25

41334 Nettetal-Leuth

Die Skulptur „Fliegende Stühle“ ist Teil der Kunst-Radroute „FahrArt“, Mai 2021- Mai 2023

ULRIKE KESSL, Fliegende Stühle, 2021

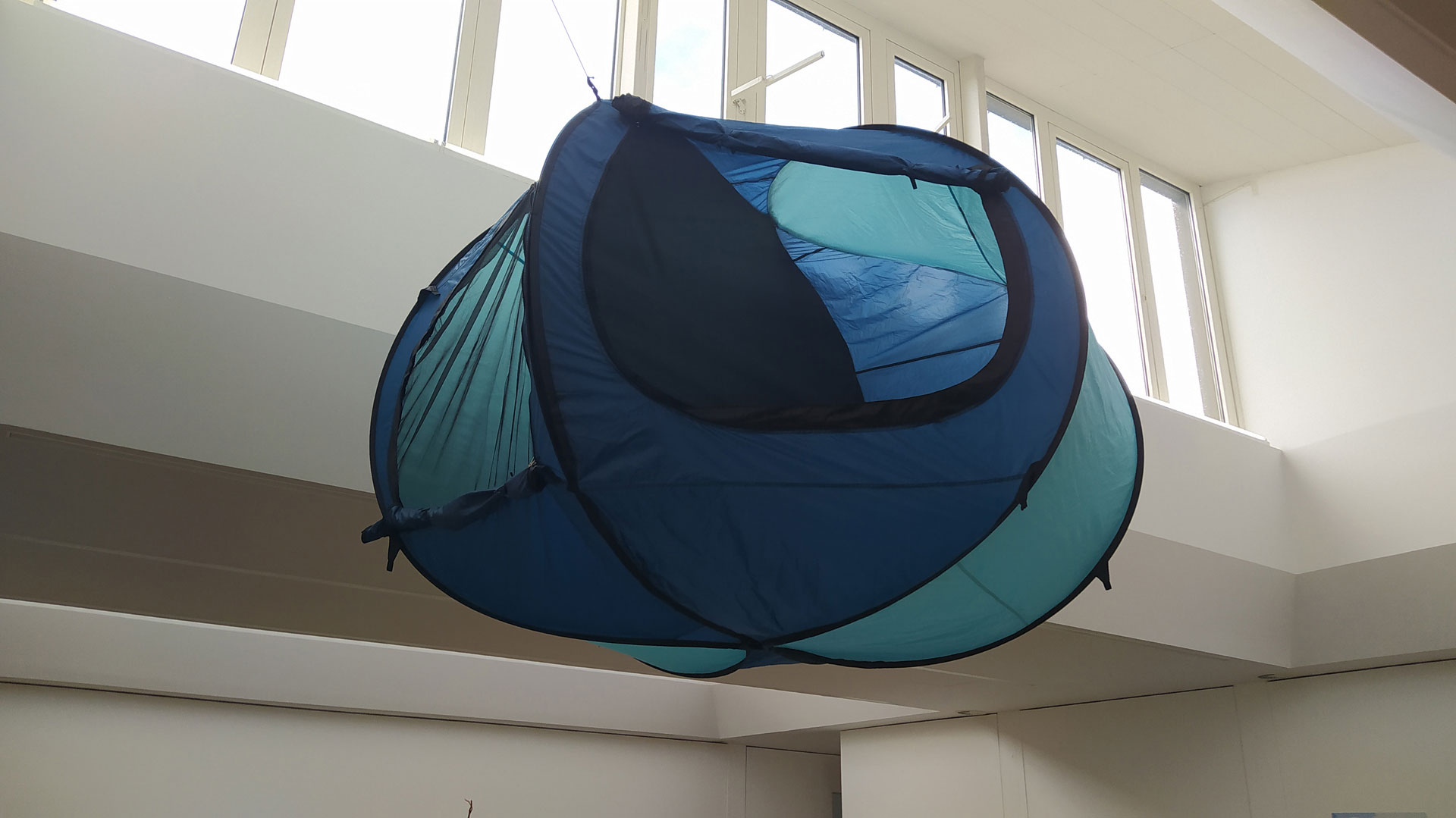

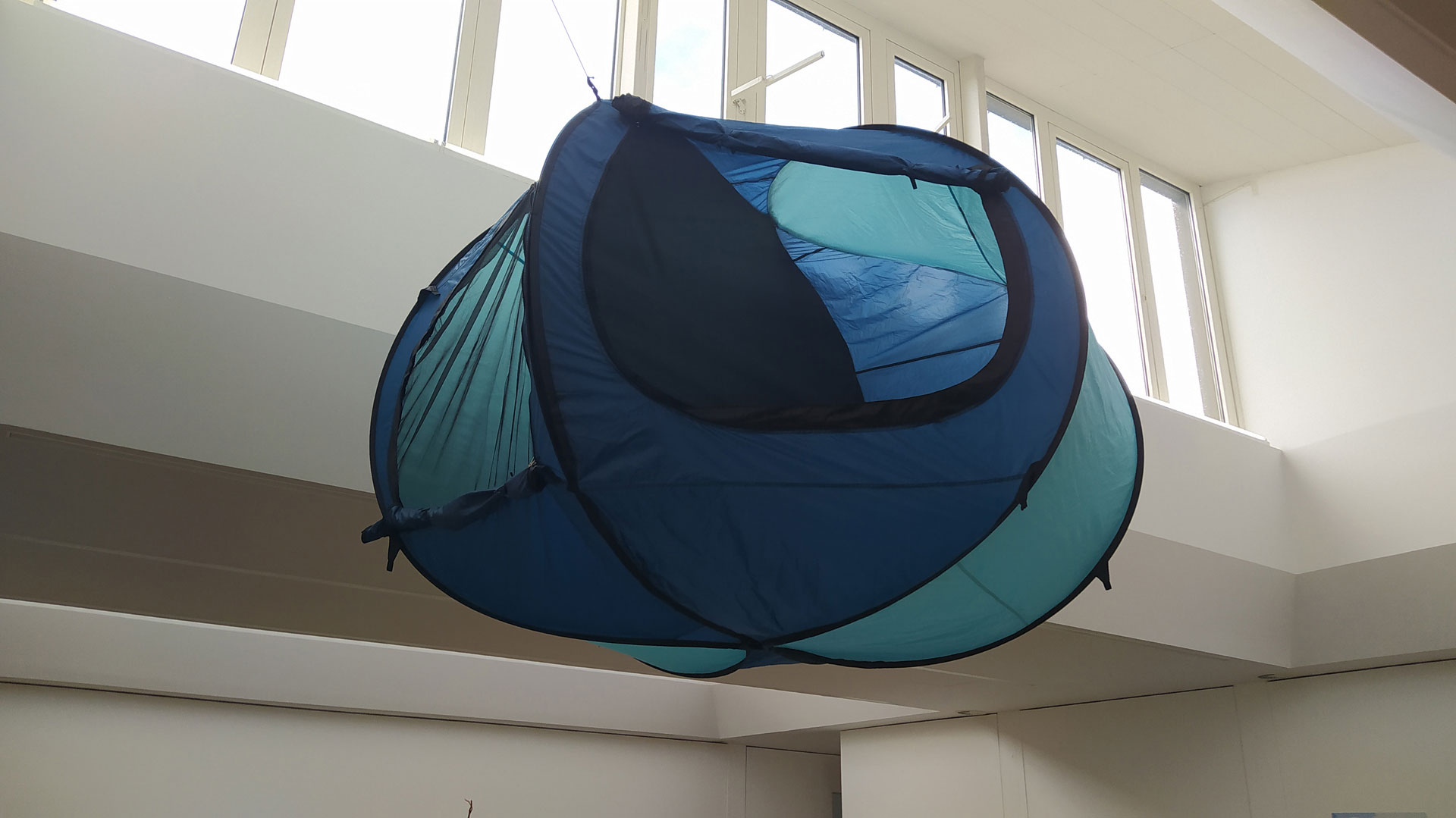

Der Traum vom Wohnen

AUSSTELLUNG

Der Traum vom Wohnen

Museum Ratingen, 7. Mai – 1. November 2021

KünstlerInnen: Hörner/Antlfinger, Ulrike Kessl, Neringa Naujokaite, Driss Ouahadi, Veronika Peddinghaus

ULRIKE KESSL, Zeltkapsel, 2019

ULRIKE KESSL, Ensemble living“ (7teilig), 2021

ULRIKE KESSL, Ensemble living“ (7teilig), 2021

Kunst und KSK II

AUSSTELLUNG

KUNST & KSK II

kunst raum rottweil, 16. Mai – 19. September 2021

Ausstellungsflyer

Bühne der verkörperten Begegnung

TEXTE

Rita Kersting, 1997

Bühne der verkörperten Begegnung

Die Waage ist ein recht unbarmherziges Instrument, das nichts weiter tut

als eine Zahl zu zeigen, die das Gewicht unseres Körpers angibt. Es ist

eine anonyme, jedoch spezifische, eine objektive, jedoch individuelle

Ziffer,die uns erschreckt oder erfreut, abhängig von den Erwartungen und

vorangegangenen Maßhaltungen, mit denen wir die Waage besteigen. Oft

jedoch hinterläßt die Selbstbegegnung mit dieser abstrakten Zahl,

ähnlich wie beim Lesen der persönlichen Paßnummer, eine Leere, eine

innere Gleichgültigkeit. Sie bestätigt unsere Existenz, teilt uns aber

über uns selbst nichts mit.

Ulrike Kessl hat in Rheine eine Waage auf dem `Thie´ platziert, die

dreißig Jahre lang in einer Textilfabrik Garnspulen auswog. Dieser

Funktion enthoben erhält die Waage im Ausmusterungsalter an öffentlichem

Ort eine neue, die Kessl ermöglicht, aber nicht ausformuliert. Die

große Wiegefläche ist bündig in den Boden eingelassen, so daß keine

Hemmschwelle die Bummelnden von der Benutzung des Kunstwerks abhält, das

sich auf den ersten Blick ästhetisch von den platzgestaltenden

Schildern, Baumgittern und Laternen nicht unterscheidet, gleichwohl bei

näherer Betrachtung einen deplatzierten und leicht absurden Eindruck

macht. Dabei greift Ulrike Kessl mit der Waage auf ein traditionell von

öffentlicher und nicht von Künstlerhand aufgestelltes Instrument zurück,

das öffentliche Plätze seit dem Mittelalter als Orte des Handels

kennzeichnete.

Nicht als allansichtige, materialschwere und `schöne´Skulptur ist die ”

Statt-Waage” allein zu betrachten, sondern als Werkzeug, dessen Funktion

erst beim Betreten aktiviert wird. Eine theatrale Dimension bereichert

somit das keineswegs nur autonome Kunststück, das als Intervention das

Augenmerk auf die örtliche Situation und die Rezipienten lenkt.

Mit der Verlagerung der privaten, normalerweise in der Intimität des

eigenen Badezimmers stattfindenden Handlung auf den Rheiner `Thie´ wird

die Wiegefläche zur Bühne, die einen grenzenlosen Übergang von

Zuschauer, Benutzer und Kunstwerk gewährleistet. Die individuelle

Körperkontrolle gerät so zum kollektiven Ereignis, die private Handlung

zur öffentlichen Aufführung.

In unserer Zeit, in der sich Plätze von Nachbarschaftstreffpunkten zu

Parkplätzen, Einkaufszonen oder Verkehrsknotenpunkten entwickeln und

sich das Leben hinter die Fensterrolläden, vor den Fernseher

zurückzieht, erfährt der öffentliche Raum eine tiefe Krise. Mit

zunehmender Isolierung und der Möglichkeit per Telefon, Fax und E-mail

körperlos in Kontakt zur Außenwelt zu treten, verwaisen öffentliche

Plätze oder werden zur Heimstatt von verschiedenen Randgruppen unserer

Gesellschaft. Den Überraschungen und unvorhergesehenen Begegnungen, die

auf öffentlichen Plätzen erlebt werden können, entziehen sich die

Menschen immer häufiger durch Abwesenheit. Kessls “Statt-waage” erinnert

an unseren Körper sowohl durch ihre anthropomorphe Gestalt als auch

durch das Wiegen desselben. Begegnungen mit sich selbst und mit anderen

sind auf ihr möglich, dabei bildet der Körper als Materie eine Prämisse,

die in Zeiten zunehmender Immaterialität nicht selbstverständlich.

Rita Kersting

Clothing

TEXTS

Emmanuel Mir, 2016

Clothing

Let’s get to the point straight away, without any prelude or elaborate

introduction, and state bluntly but accurately that while the objects,

installations and assemblages of Ulrike Kessl, as she has been

increasingly creating them from various articles of clothing over the

past decade, inevitably lead to associations with the body, the human

body is by no means here her theme.

When nylon tights are stretched across the facade of a historical

building (Monument for Örebro) or between the four walls of a gallery

(Nylons in Space), when photography of dresses and blouses are sewn onto

a textile background (Islands) or safety vests linked up to form a

funnel hanging on the ceiling (Syövest), the viewer may be inclined to

see metaphors for the human form in these textile sculptures. That

would, however, be a conditioned reflex, a kind of intellectual

short-circuit that has gained currency in art appreciation over the past

half century. But in Ulrike Kessl’s works the focus is not on the body,

but on space. Her positioning of items of clothing and various textiles

reveals and highlights the physical and atmospheric features of the

room in which they appear. Both the material components (the dimensions,

colours, materials and composition, etc.) as well as the subjective

vibrancy of natural or architectural space are rendered visible in these

textile settings – sometimes highlighted and emphatic, sometimes

narrated.

It was necessary to clear up at the outset any possible

misunderstandings in the reception of Ms. Kessl’s work as the body

metaphor is pervasive and stubborn. In the context of visual art, it is

difficult to resist the narrative power of clothing, especially used

clothing. Whether as sculpture, installation or object, the isolated,

out-of-context garment evokes the human body and its various –

political, biographic or social – dimensions. The tradition of artists,

and primarily female artists, employing this element is long. From Meret

Oppenheim, Lygia Clark and Marie-France Guilleminot to Rebecca Horn –

the use of a modified and worked second skin is usually intended to draw

reference to the first. The political context also cannot be denied –

the body, this on-going battlefield of individuation in the

post-structural sense, is an eminent political entity, and its

artificial covering can be considered a visible symptom of invisible,

psychological and social processes. When specifically female artists

work with textiles as a medium, the feminist and gender ramifications

would seem to be rather obvious. This is due above all to certain

intellectual and sexual trends. The early 1990s, when Ulrike Kessl was

creating her first works and already making her mark in the art scene,

can now be seen as a particularly prolific decade for the genre of

“clothes sculptures”.1 This period saw a rise in the number

of female artists who were taking the surfaces of textiles as a medium

for their endeavours and with these coverings were exploring various

aspects of individuality. The Moss Coat by Leslie Fry, the long gowns of

Beverly Semmes, the eccentric costumes of Klaar van der Lippe or the

printed overcoat by Alba D’Urbano were all created at this time and

enjoy high visibility in the art world. Whether as installation or, and

in particular, when they are used en masse, the material communicates a

memento mori character, which can be seen most clearly in the works of

Annette Messager or Christian Boltanski. The worn clothing were then

used as a “lane of memory”2 and accordingly show a high degree of emotionality.

Whether as an object or an installation: The connotations raised by

textile sculptures have become so cemented in contemporary art that a

disinterested use of this form is now practically impossible. Ulrike

Kessl nevertheless attempts to reinterpret the material. When she

started working increasingly with textiles, she was well aware that she

was approaching the interpretative danger zone of the body metaphor.

Perhaps with a view to neutralising this risk, she initially focussed on

unprocessed materials, where the relationship to the body was not so

evident. In the Landscape series (1997) that she developed in Marfa,

Texas, or in Staircase (1994) and Brain (1998), the artist constructed

space of calico and muslin, which with their clear lines and their

purposeful, non-narrative presence, were defined architecturally. The

viewer’s body was of course never excluded from these space constructs –

on the contrary: theses spaces always had to be physically experienced;

nevertheless the association with intimate, individual bodies fell

further into the background in favour of a phenomenological exploration

of the spatial features present.

As if a reminiscence of these earlier works, some of the more recent

creations of Ulrike Kessl seek friction with the viewer. In Running

Clothes (2009), for example, the recipient’s body comes in direct

contact with the coloured nylon tights hanging on cables. In contrast to

Rutrill (2014) or the Monument for Örebro (2015), both of which imply a

frontal and therefore distanced reception, the physical confrontation

with the space is one central aspect of the installation. The visitor

penetrating the tunnel-like space of the Field Institute on the

Hombroich museum island, also finds himself physically very close to the

textile objects. It must, however, be emphasised that Running Clothes

was conceived especially for spatially difficult, elongated Field

Institute with its very sparse natural light. The nylon tights are

positioned as counterpoints in this space, their vertical lines

highlighting the dominant horizontal character of the location. Their

colours also create a stark contrast to the cold inhospitality of the

(albeit untypical) White Cube. The tights thus cause the visitor to

intensify his view, to intensify his perception. The room is not only

the carrier and the container; it is transformed into an autonomous

body, whose features become (more) amenable to the visitor with Kessl’s

intervention. In short: Running Clothes is a site-specific installation,

and like every site-specific installation, the main focus is on aspects

of space. The site-specific argument will in itself suffice to

invalidate mere psychological or narrative interpretations of the work

of Ulrike Kessl.

One interesting aspect of this work is the interaction between distance

and proximity. We have already hinted as this effect: works such as

Rutrill or Monument for Örebro keep the viewer at a distance – in strong

contrast to Running Clothes. The two-part Rutrill installation was

realised for the Lemgo art society and consists, in one part, of

colourful pairs of nylon tights fixed to an extension behind the

Eichenmüllerhaus building, while the other part is a monochrome line

made up of more pairs of tights stretched between two trees in the

adjacent garden. The sense of distance here is generated by the number

of works. A viewer can perceive the overall image of the clad facade

(“clad” to be understood here in the architectural sense) only at a

distance of at least twenty metres, while for the significantly larger

work at the Örebro town hall a further twenty metres are necessary. The

receiver is therefore prevented from recognising the overall structured

design and its detailed surface structure at the same time; he has to

move back and forth in order to link the two parts of the visual

information. A similar situation can be found in Rondo (2015), which is

suspended high above he heads of walkers, or Halbwolke (2010), which

also remains unreachable, whether in the interior or the exterior

version. By strategically positioning her installations at points that

provoke distance among visitors, Ulrike Kessl determines the focus and

controls the perceptive rhythm. The version of Nylon in Space (2015)

appearing in the city of Wuppertal on the other hand conjures up a sense

of closeness that recalls that generated by Running Clothes. The

visitor’s body is again here incorporated directly in the work, become

an integral part of the installation, caught in space like a fly in a

web.

With the maximum tensile extension of Nylon in Space, the nylons lose

all reference to their original function – they now function only as a

material, objects that are defined primarily by their elastic features.

They are, however, first and foremost elements that animate and

structure space and, perhaps, work counter to the existing room

structure. Again here we can discover an antithetical moment in Kessl’s

contribution. Because the interior architecture of Neuer Kunstverein is

dominated by horizontals and verticals and because the massive pillars

radiate weight and slowness, the artist has placed colourful diagonals,

that create an airy, illuminating and invigorating effect. The room is

then scarcely recognisable. Or: You simply have to see it with entirely

new eyes.

A similar challenge was presented by the thankless corner in the Wilhelm

Lehmbruck Museum in Duisburg, where Ulrike Kessl installed a different

version of Nylon in Space. Thankless, because it is highly unsuitable

for conventional exhibition of art works, with its tiny window corner

interrupting the flow of the wall surface and with the light rails on

the ceiling providing yet another visual disturbance. But this is

precisely where Ulrike Kessl applies her imagination and skill,

stretching her nylon net out to solve all that spatial awkwardness. The

installation becomes an ornament giving the room a new homogeneity and

dynamism. These two installations show clearly how Ms. Kessl seeks out

challenges and gets fulfilment in tackling problems posed by complicated

architectural space. The nylon tights are in this sense an adequate and

humorous response to “impossible locations”: Just like an invasive

plant species with a high physical adaptability, they nestle up to every

structure and transform it for the brief duration of the intervention.

The material is, however, also so light and delicate that it does not

impede on or smother its environment. Nylon tights can cope with every

space and room, but without making it disappear completely.

The nylon tights are either bought new or – simply because the artist

requires a large volume of them – used as used pairs. In the latter

case, they are first collected, generally on the basis of a local appeal

for donations of unwanted items, and then dyed, although their original

colour does give the creation a special touch. The artist naturally

arranges the colour combinations after careful consideration, composing

with varying shades of a basic colour (Rondo, 2015) or, in other cases,

working with striking contrasts (Nylons in Space, 2015/16). A comparison

with painting would, however, be an exaggeration. The colour is rather

to be seen as a signal, as a marker in space, easily identifiable even

from a distance. It readily draws the attention into the landscape and

emphasises the function of the textile objects as eye-catchers.

Tension, lightness and dynamism characterise Ulrike Kessl’s sculptural

works of. Und: something is always handing down from the ceiling or from

the wall. Art in suspension. Art seeking a vertical. Art refusing to

accept gravity and preferring air as its support (a very unusual

tendency in the field of sculpture). As was the case with Nylon in

Space, Halbwolke (2010) exists in two distinct versions. The first was

suspended from trees in a garden on the Rhine, while the other was fixed

between two balconies in the staircase of the Bucharest agricultural

museum and floated gently above its atrium. This installation emerged

from a trip by the artist to Rumania, where she got to know the

Moldavian monasteries with their characteristic gently curved roofs,

recalling stylish and broad bonnets. Halbwolke (Half-cloud) provides a

fine example of how Ulrike Kessl can neutralise any potential narrative

or atmospheric factors in her work. Despite the title being stipulated,

the illusion should not include too much space – it is not a small

cloud, but rather a half-cloud. A red border was therefore sewn in that

intentionally thwarts any narrative implication of the work. More than a

mere object (cloud, jellyfish, flower, boat, UFO, etc.) or more than

the stylised memory of an object from the real world, Halbwolke is

primarily a form, a form with a specific physical identity, but without

narrative reference, without history, without anecdote. An abstract and

therefore general form, one not reduced to any special association.

We are, however, unable to deny a certain association with a certain

part of art history: that of the baldachin or canopy. This ornate cover

over a throne, an altar or a bed is – contrary to common assumption –

never a purely decorative element. The baldachin achieves above all a

marking. It highlights a particular point, emphasising that the object,

or subject, present underneath is noble or even sacred. Baldachins are

accordingly also found in enclosed spaces, such as a church, a relic

shrine or a tomb. The baldachin provides not only protection, it is

especially a symbol and a visualisation of power and dignity. It

ostentatiously draws attention to the elevated status of the people or

the space beneath. This marking function can be recognised in various

works of Ulrike Kessl – in Rondo, in Rutrill und in Syövest (2016). With

their positioning in prominent places in interiors and exteriors, Ms.

Kessl creates a distinct special zone in the landscape and ensures more

focused and intensive attention on this zone. This fact underlines again

the remark we made above regarding function of colour in these

installations: each arrangement sends a signal, a challenge, to perceive

the genius loci of the place more carefully.

In this spatially defined working context, the image assemblages of

Ulrike Kessl generate an additional reflection medium removed from any

local idiosyncrasies of the site. Piles of shirts, bras, pants and other

textiles are arranged according to shades of colour so that a uniform

overall impression is created and is then grouped and photographed in

“Islands”, as the title of the series indicates. In a further step, the

medium-sized photographs are sewn onto carpets, such that their picture

characteristics are transformed, oscillating in an object-like

appearance between flatware and a spatial object. These are each

independent creations, without any reference to existing installations

and not even conceived as a concept aid for future realisations; to see

them as mere sketches would be a misunderstanding. These formal

experiments, sounding out potential opportunities for a work with

acquired used items of clothing, are present in order to highlight

certain aspects of Ms. Kessl’s artistic production. The form, the play

with volumes and with vacant spaces, the tears and fissures and the

drapes, the texture of the various surfaces and the circumspect

variations of the different designs come to the fore here.

Above all in this assemblage cycle can we recognise the significance of

the materiality in the work of Ulrike Kessl. Repeating this point we can

finally close the circle: The artist’s heedfulness of surface structure

and materiality of her medium reveals the special nature of her

approach while also marking a clear delineation in relation to other

textile works of art in contemporary art. The sculptress Ulrike Kessl

has accepted the challenge posed by a material that, while full of

narrative and art historical references and is temptingly open to

psychological interpretation, nevertheless primarily holds physical,

material characteristics and is employed here to formulate commentaries

on specific spaces. In this work, therefore, the human body is an

instrument of perception and not a thematic focus.

Emmanuel Mir

1. See, for example, the exhibitions “Empty Dress –

Clothing as Surrogate in Recent Art” in ICI New York (1993), “Discursive

Dress” in the Kohler Art Center, Sheboygan (1994) or “Metaphors. The

Image of Clothing in Contemporary Art” in Huntsville Museum of Art

(1989).

2. Cora von Pape: Kunstkleider – Die Präsenz des Körpers in textilen Kunst-Objekten des 20. Jahrhunderts, Bielefeld 2008.

Verkleidungen

TEXTE

Emmanuel Mir, 2016

Verkleidungen

Abrupt, aber pointiert möchten wir sofort auf den Punkt kommen, ohne

Vorspiel und raffinierte Einleitung: Die Objekte, Installationen und

Assemblagen von Ulrike Kessl, die sie seit zehn Jahren verstärkt aus

diversen Kleidungsstücken entstehen lässt, schaffen zwar eine

unumgängliche Assoziation zum Körper – aber um den Körper geht es hier

mitnichten.

Wenn Strumpfhosen an der Fassade eines historischen Gebäudes (Monument

für Örebro) oder zwischen den vier Wänden einer Galerie (Nylons in

Space) aufgespannt, wenn Fotos von Kleidern und Blusen auf einen

textilen Hintergrund genäht (Inseln) oder Warnwesten miteinander

verbunden und trichterartig an die Decke gehängt werden (Syövest),

könnte der Rezipient geneigt sein, Metaphern des menschlichen Körpers in

diesen Stoffplastiken zu sehen. Dies wäre ein interpretatorischer

Reflex, ein in der Kunstrezeption der letzten fünfzig Jahre erlangter

intellektueller Kurzschluss. Bei den Arbeiten von Ulrike Kessl steht

aber nicht der Körper im Vordergrund, sondern der Raum. Durch den

Einsatz von Kleidungsstücken und Stoffen kommen die physischen und

atmosphärischen Eigenschaften des Raumes zur Geltung. Sowohl die

sachliche Komponente (Maße, Farben, Materialien, Verhältnisse etc.) als

auch die subjektive Ausstrahlung von natürlichen oder architektonischen

Räumen werden in diesen textilen Setzungen sichtbar gemacht – manchmal

betont und hervorgehoben, manchmal bloß kommentiert.

Gut, dass wir somit das potenzielle Missverständnis in der Rezeption von

Kessls Arbeit aus dem Weg geräumt hätten. Denn die Körpermetapher von

textilen Kunstwerken ist hartnäckig. Im Kontext der Bildenden Kunst ist

die narrative Kraft von Kleidern, insbesondere wenn sie aus Second Hand

stammen, verführerisch. Als Skulptur, Plastik oder Objekt beschwört das

isolierte, verfremdete Kleidungsstück den Körper und seine diversen –

politischen, biografischen, sozialen – Dimensionen herauf. Die Tradition

von Künstlern, und vor allem von Künstlerinnen, die darauf

zurückgegriffen haben, ist lang. Von Meret Oppenheim, Lygia Clark und

Marie-France Guilleminot bis zu Rebecca Horn – der Einsatz einer

modifizierten und präparierten zweiten Haut ist immer ein Hinweis auf

die erste. Der politische Hintergrund ist dabei nicht zu leugnen. Der

Körper, dieses aus poststrukturalischer Sicht dauerhafte Schlachtfeld

der Individuation, ist eine eminente politische Entität, und seine

künstliche Hülle gilt als sichtbares Symptom von unsichtbaren,

psychologischen oder sozialen Prozessen. Gerade wenn Künstlerinnen sich

mit dem Medium Stoff auseinandersetzen, scheint die Einbettung in einen

feministischen bzw. Gender-Kontext so gut wie unausweichlich. Dies ist

vor allem bestimmten intellektuellen und ästhetischen Moden geschuldet.

Die frühen 1990er Jahre, als Ulrike Kessl ihre ersten Arbeiten

realisierte und bereits Fuß im Kunstbetrieb fasste, erweisen sich in

dieser Hinsicht als eine besonders fruchtbare Dekade für die Gattung der

„Kleiderskulpturen“.1 Damals mehrte sich die Zahl an

Künstlerinnen, die die Oberflächen von textilen Stoffen als Medium ihrer

Arbeit nahmen und mit dieser Hülle die Tiefe des menschlichen

Individuums hinterfragten. Der Moos-Mantel von Leslie Fry, die

überlangen Kleider von Beverly Semmes, die exzentrischen Kostüme von

Klaar van der Lippe oder die bedruckten Überzieher von Alba D’Urbano

entstehen zu diesem Zeitpunkt und genießen eine starke Sichtbarkeit in

der Kunstwelt. Als Installation, und vor allem wenn sie en masse

verwendet werden, haftet dem Material ein Memento-mori-Charakter an, am

deutlichsten in den Arbeiten von Annette Messager oder Christian

Boltanski herauszulesen. Die getragenen Kleider werden dann als „Spur

zur Erinnerung“2 eingesetzt und besitzen daher einen hohen Grad an Emotionalität.

Ob als Objekt oder als Installation: Die Konnotationen der

Stoffskulpturen haben sich in der zeitgenössischen Kunst so gefestigt,

dass ihre unvoreingenommene Verwendung kaum noch möglich zu sein

scheint. Und doch wagt sich Ulrike Kessl an eine Umdeutung des

Materials. Als sie anfing, zunehmend mit Textilien zu arbeiten, war

Kessl darüber bewusst, dass sie sich der interpretativen Gefahrenzone

der Körpermetapher näherte. Vielleicht um diese Gefahr zu

neutralisieren, legte sie zunächst den Schwerpunkt auf raue Stoffe,

deren Bezug zum Körper nicht evident war. In der in Marfa, Texas,

entstandenen Landscape-Serie (1997) oder in Treppenhaus (1994) und

Gehirn (1998) baute die Künstlerin Räume aus Nessel und Musselin, die

mit ihren klaren Linien und ihrer sachlichen, nicht erzählerischen

Präsenz, architektonisch definiert waren. Selbstverständlich war der

Körper des Betrachters aus diesen Raumkonstrukten nie ausgeschlossen –

im Gegenteil mussten diese Räume physisch erfahren werden –, aber der

Zusammenhang mit intimen, individuellen Körpern geriet in den

Hintergrund zugunsten eines phänomenologischen Auslotens der gegebenen

Raumeigenschaften.

Wie als Reminiszenz an diese frühen Werke suchen manche neueren Arbeiten

von Kessl die Reibung mit dem Betrachter. In Running Clothes (2009)

beispielsweise tritt der Körper des Rezipienten in direkten Kontakt mit

den gefärbten Strumpfhosen, die an Seilzügen hängen. Anders als Rutrill

(2014) oder als das Monument für Örebro (2015), die beide eine frontale

und daher distanzierte Rezeption implizieren, ist die physische

Auseinandersetzung mit dem Raum ein zentraler Aspekt der Installation.

Der Besucher, der in den tunnelartigen Raum des Field Institute auf der

Museumsinsel Hombroich eindringt, kommt sehr nah an die textilen

Gegenstände heran. Es muss aber unterstrichen werden, dass Running

Clothes speziell für das an sich räumlich schwierige, langgezogene und

mit natürlichem Licht kaum ausgestattete Field Institute konzipiert

wurde. Die Strumpfhosen werden als Kontrapunkte in dem Raum eingesetzt,

ihre vertikale Ausrichtung betont den vorherrschenden horizontalen

Charakter des Ortes. Ihre Farbgebung schafft zudem einen starken

Kontrast zur Kälte und Unwirtlichkeit des (gewiss untypischen) White

Cube. Die Strumpfhosen bewirken also eine Intensivierung des Blicks,

eine Schärfung der Wahrnehmung. Der Raum ist nicht nur Träger und

Behälter; er wird zu einem autonomen Körper gemacht, dessen

Eigenschaften man sich durch Kessls Intervention bewusst(er) wird. Summa

summarum: Running Clothes ist eine Site-specific-Installation, und wie

jede Site-specific-Installation wird der Schwerpunkt auf Raumaspekte

gelegt. Das Site-specific-Argument reicht an sich aus, um psychologische

oder narrative Interpretationen in der Arbeit von Ulrike Kessl zu

entkräften.3

Ein interessanter Punkt dieser Arbeit betrifft die Wechselverhältnisse

zwischen Distanz und Nähe. Wir haben es bereits angedeutet: Werke wie

Rutrill oder Monument für Örebro halten den Rezipient auf Distanz – ganz

anders als Running Clothes. Die zweiteilige Installation Rutrill wurde

für den Kunstverein Lemgo realisiert und besteht einerseits aus bunten

Nylonstrumpfhosen, befestigt an dem Vorbau des Eichenmüllerhauses, und

anderseits aus einer monochromen Linie von weiteren Strumpfhosen, die

zwischen zwei Bäumen im Garten des Hauses hängen. Die Distanzierung

entsteht hier durch die Vielzahl der Arbeiten. Der Betrachter kann das

ganze Bild der verkleideten Fassade („verkleidet“ ist hier im

architektonischen Sinne zu verstehen) nur aus gut zwanzig Meter Abstand

wahrnehmen. Und für die deutlich größere Arbeit am Rathaus von Örebro

sind zwanzig Meter mehr vonnöten. Es bleibt also dem Rezipienten

verwehrt, den gesamtgestalterischen Entwurf und dessen detaillierte

Oberflächenstruktur gleichzeitig zu erfassen; er muss hin und her gehen,

um die zwei verschiedenen Informationen zu verknüpfen. Ähnlich verhält

es sich mit Rondo (2015), das hoch über den Köpfen der Spaziergänger

hängt, oder mit Halbwolke (2010), die, egal ob es sich um die Innen-

oder Außenraum-Version handelt, unerreichbar bleibt. Durch die

strategische Platzierung ihrer Installationen an Stellen, die ein

Fernhalten des Betrachters provozieren, gibt Ulrike Kessl einen Fokus

vor und bestimmt den perzeptiven Rhythmus. Dagegen ruft die Wuppertaler

Fassung von Nylon in Space (2015) eine Nähe hervor, die stark an die von

Running Clothes erinnert. Auch hier ist der Körper des Besuchers

unmittelbar in das Werk einbezogen; hier ist der Leib des Rezipienten

ein integraler Bestandteil der Arbeit, gefangen im Raum wie eine Fliege

im Spinnennetz.

Mit der maximalen Spannkraft von Nylon in Space verlieren die

Strumpfhosen jedwede Referenz zu ihrer ursprünglichen Funktionalität.

Hier fungieren sie nur noch als Material. Es sind Gegenstände, die in

erster Linie durch ihre elastischen Eigenschaften definiert werden. Es

sind aber vor allem Elemente, die den Raum animieren und strukturieren

bzw. gegen die vorhandene Raumstruktur arbeiten. Auch da entdeckt man

ein antithetisches Moment in Kessls Vorschlag. Weil die Innenarchitektur

des Neuen Kunstvereins von Horizontalen und Vertikalen dominiert ist

und weil die massiven Pfeiler Schwere und Behäbigkeit ausstrahlen, setzt

die Künstlerin bunte Diagonalen, die luftig, leuchtend und lebendig

wirken. Der Raum ist nicht mehr zu erkennen. Oder: Man muss ihn mit ganz

neuen Augen sehen.

Ähnlich ist die undankbare Ecke im Wilhelm Lehmbruck Museum von

Duisburg, in dem Kessl eine andere Version von Nylon in Space

installiert. Undankbar ist die Ecke schon, weil sie sich mit ihrer

winzigen, die Wandfläche unterbrechenden Fensterecke und mit der

Klimaanlage an der Decke, die eine weitere visuelle Störung hervorruft,

für herkömmliche Kunstpräsentationen nicht eignet. Genau da aber nistet

sich Ulrike Kessl ein und dehnt ihr Nylonnetz aus, um all die

schwierigen Raumumstände zu tilgen. Die Installation wird zu einem

Ornament, das den Raum homogenisiert und dynamisiert. An diesen zwei

Installationen wird deutlich, wie Kessl die Herausforderung sucht und

sich gerne an architektonisch schwierigen Räumen reibt. Die

Nylonstrumpfhosen sind in dieser Hinsicht eine adäquate und witzige

Antwort auf „unmögliche Orte“: Wie eine invasive Pflanzenart mit hoher

Anpassungsfähigkeit schmiegen sie sich an jede Struktur und verändern

diese für die kurze Zeit der Intervention. Zugleich aber ist das

Material so leicht und zart, dass es seine Umwelt nicht erdrückt oder

erstickt. Mit den Nylonstrumpfhosen lässt sich jeder Raum bewältigen,

ohne jedoch ihn vollständig verschwinden zu lassen.

Die gebrauchte Natur der Strumpfhosen ist übrigens nicht ganz

unbedeutend, denn sie sorgt für die individuelle Farbigkeit jedes

einzelnen Stücks – und damit für die chromatische Vielfalt der

Installationen und Interventionen. Nach dem Prozess ihres Sammelns, der

meistens aus einer lokal durchgeführten Aufrufaktion hervorgeht, wird

die Nylonware gefärbt, wobei ihre Ursprungsfarbe ihnen eine besondere

Note verleiht. Selbstverständlich geht Kessl bewusst mit der

Zusammensetzung der Farben um und komponiert mit Abstufungen eines

Grundtons (Rondo, 2015) oder arbeitet im Gegenteil mit eklatanten

Kontrasten (Nylons in Space, 2015/16); aber von einem Bezug zur Malerei

zu sprechen, wäre hier übertrieben. Die Farbe ist vielmehr als Signal zu

verstehen, als Kennzeichnung im Raum, leicht und aus weiter Entfernung

sichtbar. Sie zieht den Blick in die Landschaft unweigerlich an sich und

betont die Funktion der textilen Objekte als Eye-Catcher.

Spannung, Leichtigkeit und Dynamik charakterisieren die plastische

Arbeit von Ulrike Kessl. Und: Immer hängt etwas von der Decke oder von

der Wand herunter. Eine Kunst im Schwebezustand. Eine Kunst, die die

Vertikale sucht. Eine Kunst, die die Statik nicht akzeptiert und die

Luft als Element bevorzugt (eine für die Gattung der Plastik

außergewöhnliche Neigung). Wie Nylon in Space existiert Halbwolke (2010)

in zwei distinkten Versionen. Die erste hing an Bäumen in einem Garten

am Rhein, die andere wurde im Treppenhaus des Bukarester Bauernmuseums

angebracht und schwankte leicht über dessen Atrium. Die Installation

entstand nach einer Reise der Künstlerin nach Rumänien, bei der sie die

Moldauklöster mit ihren typischen geschwungenen, an feine und breite

Hauben erinnernden Dächern kennenlernte. Halbwolke gibt exemplarisch

vor, wie Kessl die potenziell narrativen oder atmosphärischen Faktoren

ihrer Arbeit neutralisiert. Trotz der Vorgabe des Titels soll die

Illusion nicht allzu viel Raum erhalten – das ist keine Wolke, sondern

eben eine Halbwolke. Deshalb wurde ein roter Saum eingenäht, der jede

erzählerische Anknüpfung absichtlich ruiniert (?). Mehr als ein Ding

(Wolke, Qualle, Blume, Schiff, UFO etc.) oder mehr als die stilisierte

Erinnerung an ein Ding aus der Realwelt ist Halbwolke in erster Linie

eine Form. Eine Form mit einer spezifischen physischen Identität, aber

ohne narrative Referenz, ohne Geschichte, ohne Anekdote. Eine abstrakte

und daher allgemeine, nicht auf eine bestimmte Assoziation reduzierbare

Form.

Eine Assoziation aus dem kunsthistorischen Bereich können wir uns aber

nicht verkneifen: die des Baldachins. Das über dem Thron, dem Altar oder

dem Bett aufgebaute Zierdach ist – anders als allgemein gedacht – kein

reines dekoratives Element. Der Baldachin schafft vor allem eine

Markierung. Er hebt eine besondere Stelle hervor, verdeutlicht, dass das

sich darunter befindende Objekt/Subjekt edel oder gar heilig ist.

Deshalb findet man auch Baldachine in abgeschlossenen Räumen wie in

Kirchen, über Reliquienschreinen oder Grabmälern. Der Baldachin ist

nicht nur Schutz, er ist vor allem Symbol und Visualisierung der Macht

und der Würde. Ostentativ macht er auf die Besonderheit der Menschen und

des Raums unter ihn aufmerksam. Diese Markierungsfunktion finden wir in

verschiedenen Arbeiten von Ulrike Kessl wieder – in Rondo, in Rutrill

und in Syövest. Durch ihre Platzierung an hervorgehobenen Plätzen im

Innen- oder Außenraum erschafft Kessl eine abgegrenzte Sonderzone in der

Landschaft und setzt eine intensivere Aufmerksamkeit dessen durch.

Diese Tatsache bekräftigt die von uns weiter oben gemachte Bemerkung zur

Funktion der Farbe in diesen Installationen: Jede Setzung ist ein

Signal, eine Aufforderung, den Genius Loci genauer wahrzunehmen.

In diesem räumlich geprägten Arbeitskontext schaffen die Bildassemblagen

von Ulrike Kessl ein zusätzliches Reflektionsmedium, das sich von jeder

Ortsspezifik frei macht. Haufen von Hemden, Bustiers, Hosen und anderen

Textilien werden nach Farbtönen sortiert, so dass ein einheitliches

Gesamtbild entsteht, und in „Inseln“ – so auch der Titel der Reihe –

gruppiert und fotografiert. In einem weiteren Schritt werden die

mittelgroßen Fotografien auf Teppiche genäht. Es sind eigenständige

Skizzen, ohne Verweis auf bestehende Installationen und nicht mal als

Denkstützen für künftige Realisierungen konzipiert. Diese formalen

Experimente, die die Möglichkeiten einer Arbeit mit vorgefundenen

Kleidungsstücken ausloten, sind da, um bestimmte Aspekte der

künstlerischen Produktion von Kessl zu unterstreichen. Weil sie eben

ohne Raumeinbettung auskommen, besitzen sie einen ausgeprägten

skulpturalen Charakter (trotz ihrer zweidimensionalen Natur). Die Form,

das Spiel mit den Volumen und mit den Leerräumen, die Risse und

Faltenwürfe, die Textur der verschiedenen Flächen und die bedachten

Variationen der diversen Textilien rücken hier in den Vordergrund.

Emmanuel Mir

1. Vgl. z. B. die Ausstellungen „Empty Dress – Clothing

as Surrogate in Recent Art“ im ICI New York (1993), „Discursive Dress“

im Kohler Art Center, Sheboygan (1994) oder „Metaphors. The Image of

Clothing in Contemporary Art” im Huntsville Museum of Art (1989).

2. Cora von Pape: Kunstkleider – Die Präsenz des Körpers in textilen Kunst-Objekten des 20. Jahrhunderts, Bielefeld 2008.

3. Obwohl wir noch ein Argument hätten, das gegen die Körpermetapher

spricht: Für die Nachwelt und für diejenigen, die die Wirkung von

Running Clothes nie leibhaftig erlebt haben, bleibt zur Erfassung der

Arbeit also nur – wie für eine Performance – das hier reproduzierte

fotografische Material übrig. Auffällig ist in diesem Punkt, dass Kessl

auf Ansichten verzichtet, die den Rezeptionsakt festhalten, um sich auf

die reine Raumsituation zu konzentrieren. Hätte sie die Konfrontation

des Betrachters mit ihrer Arbeiten dokumentieren wollen, wären Menschen

auf diesen Bildern.

Measuring, counting, trading, selling

TEXTE

Anja Wiese, 1996

Measuring, counting, trading, selling

– The market is a venue for transaction and interaction and what would it

be without the weighing scales as instrument for measuring quantities.

An arrangement of scales on the art market as a ground sculpture that

can be mounted reverses the role of the instrument into a marketable

commodity: just like rugs and carpets, it is sold by the square metre.

In her work for the art fair Kunstmesse Art Cologne, Ulrike Kessl turns

the tables: her installation titled “waagen” 1) is not only a

self-evident object d’art presented to the assessment and judgement of

the public. Viewers of the work rather become participants as soon as

they become physically aware of and responsive to the object they have

mounted. The work is not perceived from a distant perspective, but

rather does the viewer’s body become a central and essential object of

perception.

The personal weighing scales used for this work differ in their

contemporary form and colour, their design. As functional instruments

they are evidence of the collective stylistic preference of their time

and their individual utilisation in private households. Each item bears

witness to its distinct history and the people that used it in their

daily lives. More than any other domestic instrument, the weighing

scales represents a culture of body control. Its place is the bathroom,

its function the individualised monitoring of change in body weight.

What was originally an indispensable instrument of trading, the weighing

scales in this century came to be used by people to gauge and control

themselves. In the post-war period in Germany, it became an attribute of

economic growth, in the course of which moderation and proportion were

manifest in surplus and excess.

In “waagen” Ulrike Kessl renounces all personal signature.After the

initial creative inventiveness, her artistic activity involves a

collection and arrangement of existing objects. Just as the individual

weighing scales is a non-determing element of the installation, the

artist is an archaeologist withdrawn into her immediate individuality.

The sequential arrangement of the scales that – although different – all

perform the same function, i.e. weighing, contradicts the

anecdotal-narrative element that makes the visible functionality of

these used objects accessible. The neatly arranged variety of objects

decreases the significance of the individual element. Each individual

item is simply a replaceable part of the whole.

People using scales to monitor their physical development weigh

themselves by assigning a finite weight to their bodies as volume and

mass. They thus also reduce themselves to their material contents of

bone, organs and skin. Because weighing reduces all people to the lowest

common denominator, their body weight in kilograms and pounds, it also

underlines human equality in this very physical essence. Ulrike Kessl

does not make a theme of the body as medium and object of the senses,

but sees it in its essential materiality. This physical reductionism is

not surprising in an artist who for many years has been exploring modes

of representation for mass, weight and volume.

The fact that the visitor can mount the work “waagen” allows an

interactive relationship to develop between him and the installation

within the preordained framework of the game, with the state of the work

being changed by the presence of the visitors. The sculpture thus has

an active state and an inactive idle state. As participant in an

artistic measuring process on the arranged balancing scales, the visitor

experiences weighing as an elementary-mechanical interaction. The force

exerted by weight on the scales is reflected by the noisy swing of

their display indicators. But this trace left by our steps soon

vanishes, and the game we were allowed to play swings back to the

starting position.

Ulrike Kessl’s work “waagen” unfolds a dialectic of similarity versus

variety, of individuality versus uniformity, of freedom versus

determination. The individual play made possible by the visitor’s

participation in the work, the fun of weighing oneself and balanced

walking, is contrasted with measurement and weighing, reaction to

material presence. Weighing involves a distancing from oneself by

reducing the body to its mere weight, and just as all scales are the

same, all people are the same when on this instrument; by virtue of

their common materiality and weight they lose their individuality.

“Waagen” moreover contrasts the lesser significance of the every-day

household object used as installation material with the higher

significance of the scales as symbol of justice.

This work shows – and the truths that persist are always simple truths –

that all people have weight. It shows that we are of weight: In this

vital materiality we are all equal by having a body that weighs, grows

up and grows ill and deteriorates.

Amid the bustle of the market, the artist reminds us that, in the final

analysis, we cannot make assessments according to weight. The scales are

a just instrument in this endeavour, that permit this valuation even

when the eyes are blinded. Ulrike Kessl’s installation playfully weighs

up that which is hidden to imperfect insight behind a deceptive surface:

the value of the commodity art.

Anja Wiese

1) scales;

2) Space prohibits any further examination of this point here;

3) French “Balancer”: to hold in balance, swing, contemplate/examine, and “Labalance”: the scale

Messen, Zählen, Handeln, Verkaufen

TEXTE

Anja Wiese, 1996

Messen, Zählen, Handeln, Verkaufen

– kaum ein landläufiger Markt als Ort des Geschehens entbehrt der Waage

als Meßinstrument. Mit dem Auslegen von Personenwaagen als begehbare

Bodenskulptur auf dem Kunstmarkt wird das Instrument in Rollenumkehr

selbst zur Handelsware: wie Auslegware wird es per Quadratmeter

verkauft.

In ihrer Arbeit für die Förderkoje auf der Kunstmesse Art Cologne dreht

Ulrike Kessl den Spieß um: ihre Installation mit dem Titel “waagen” ist

nicht nur ein sich selbst darstellender Kunstgegenstand, welcher der

Bemessung und Beurteilung des Publikums angeboten wird. Vielmehr werden

die Betrachter der Arbeit zu deren Teilhabern, indem sie diese begehend

am eigenen Leib erfahren. Nicht sie bewerten das Werk dabei mit

distanziertem Blick, sondern ihr Körper wird Gegenstand der Erwägung.

Die für das Werk verwandten Personenwaagen unterscheiden sich in ihrer

je zeitgemäßen Form und Farbe, ihrem Design. Als funktionale Gegenstände

sind sie Zeugnisse der kollektiven Gestaltungsvorlieben Ihrer Zeit und

ihrer individuellen Ab-nutzung im Privathauhalt. Mit jedem einzelnen

Modell tritt uns die Vorstellung seiner Geschichte entgegen und die

Frage nach den Menschen, die dieses Ding genutzt haben mögen. Wie kein

anderer Haushaltsgegenstand steht die Waage dabei für eine Kultur der

Körperkontrolle. Ihr Platz ist das Badezimmer, ihre Funktion ist die

individualisierte Überwachung körperlicher Gewichtsentwicklung.

Ursprünglich ein unabdingbares Instrument des Handels wird die Waage

seit diesem Jahrhundert auch auf den Menschen angewandt. Im Nachkriegs –

Westdeutschland wurde sie zum Attribut eines Wirtschaftswachstums, zu

dessen Verlauf bald das Maßhalten im Überfluß gehörte.

In “waagen” verzichtet Ulrike Kessl auf jeden persönlichen Gestus.

Jenseits der Ideenfindung ist ihre künstlerische Arbeit das Sammeln und

Arrangieren der vorgefundenen Gegenstände. So wie die einzelne Waage der

Installation unbestimmender Teil ist, so ist die Künstlerin die in

ihrer unmittelbaren Individualität zurückgenommene Archäologin. Die

mengenhafte Aneinanderreihung der – zwar verschiedenen – Waagen, die

aber alle das Gleiche tun, nämlich wiegen, konterkariert das

anekdotisch-narrative Element, das die sichtbare Geschichtlichkeit der

gebrauchten Waagen transportiert. Die in Reih und Glied präsentierte

Vielfalt lässt das einzelne Stück gleichgültig werden. Das Einzelne ist

eben nur ein Teil des Ganzen und ersetzbar.

Menschen, die Waagen als Instrument der Körperkontrolle benutzen, wiegen

sich, weil sie ihrem Körper als Volumen und Masse ein Gewicht

beimessen. Gleichzeitig rduzieren sie sich damit auf ihren materiellen

Gehalt an Knochen, Organen, Haut. Indem das Wiegen alle Menschen auf

ihren kleinsten gemeinsamen Nenner, ihr Körpergewicht in Kilogramm und

Pfund, reduziert, zeigt es die menschliche Gleichheit in eben dieser

Körperhaftigkeit. Ulrike Kessl thematisiert den Körper nicht als

sinnliches Sensorium, sondern als Materie. Diese Körperauffassung ist

nicht erstaunlich für eine Bildhauerin, deren Thema schon seit Jahren

Masse, Volumen und Gewicht sind.

Das Begehen der Arbeit “waagen” durch die Besucher läßt zwischen jenen

und der Installation eine im votgegebenen Rahmen des Spiels

mitgestaltende Beziehung entstehen, denn der Zustand des Werkes wird

durch die Anwesenheit von Besuchern verändert. Insofern kennt die

Skulptur einen aktiven Bewegtzustand und einen Ruhezustand. Als

Teilnehmen/innen eines künstlerischen Bemessensprozesses auf den

ausgelegten Waagen balancierend, vollziehen Besucher das Wiegen als

elementar-mechanische Interaktion. Der Anstoß, den das Gewicht den

Waagen gibt, äußert sich im geräuschvollen Schwingen ihrer Meßblätter.

Doch diese Spuren unserer Schritte vergehen und das Spiel, das wir

treiben konnten pendelt aus.

Ulrike Kessls Arbeit “waagen” entfaltet eine Dialektik von Gleichheit

versus Verschiedenartigkeit, von Individualität versus Uniformität, von

Freiheit versus Bemessung. Das individuelle Spielen, das die

Partizipation am Werk ermöglicht, die Freude am Sich-Selbst-Wiegen und

am balancierenden Herumgehen steht dem Vermessen- und Gewogenwerden, der Reaktion auf die Materie gegenüber. Im Wiegen liegt eine den Körper auf sein Gewicht reduzierende Distanznahme zum Selbst und so wie alle Waagen gleich sind, sind alle Menschen vor ihnen gleich: indem sie

Gewicht haben, sind sie entindividualisiert. Darüberhinaus steht in “waagen” das Geringe des als Installationsmaterial genutzten,

alltäglichen Haushaltsgegenstandes der übergeordneten Bedeutung der

Waage als Symbol der Gerechtigkeit gegenüber.

Die Arbeit zeigt – und es sind stets die einfachen Wahrheiten , die

bestehen – daß alle Menschen ein Gewicht haben.Sie zeigt, daß wir

ge-wichtig sind und in dieser Wichtigkeit alle gleich: indem wir einen

Körper haben, der wiegt, wächst, erkrankt, vergeht.

Inmitten des Markttreibens erinnert uns die Künstlerin daran, daß in der

letztendlichen Bewertung nicht zu urteilen ist nach dem Gewicht. Die

Waage ist ihr dabei das gerechte Instrument, das diese Bewertung, selbst

mit verbundenen Augen, erlaubt. Ulrike Kessls Installation erwägt

spielerisch das, was sich unter der täuschenden Oberfläche dem

unzureichenden Blick verbirgt: den Wert der Ware Kunst.

Anja Wiese